In recent years, a disturbing pattern has emerged in Nigeria’s electoral system: the typical Nigerian election has seen elections increasingly find their conclusion in the courtroom rather than at the ballot box. A growing trend that has undermined public trust in democratic institutions, weakens electoral integrity, and threatens the legitimacy of elected officials.

Nigeria’s democratic experience dates back to the 1951 general elections under colonial rule — a landmark moment under the Lyttleton Constitution that allowed limited indigenous participation in governance. By 1959, Nigeria was preparing for full independence, with several political parties participating in national elections.

Post-independence, Nigeria adopted a federal parliamentary system. Elections were scheduled every four years, and the political scene seemed vibrant until a series of military coups disrupted the democratic process beginning in 1966. After several decades under military rule, democracy was restored in 1999 with the emergence of the Fourth Republic.

Since then, Nigeria has conducted general elections in 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023. While each cycle has brought incremental reforms, issues like voter suppression, ballot box snatching, and electoral violence remain persistent challenges.

Efforts to improve credibility, such as introducing the Biometric Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) and electronic result transmission, were meant to enhance transparency. However, lapses in implementation and limited enforcement of electoral laws have limited their impact.

Equally troubling is the increasing reliance on courts to resolve electoral disputes, often months after the people have cast their votes. This has made the judiciary a de facto final arbiter of elections — a role that should belong to the electorate.

Litmus Test Nigerian Election Case Studies

In the February 2023 presidential election, over 93 million Nigerians were registered to vote. While initial results declared Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the All Progressives Congress (APC) as the winner, the outcome was hotly contested.

On September 6, 2023, Nigeria’s Presidential Election Petition Tribunal dismissed the petitions filed by the Labour Party, the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), and the Allied Peoples Movement (APM), affirming Tinubu’s victory. For many Nigerians, this decision did not reflect the general mood of the public or the expectations set by INEC’s promised transparency.

The petitions raised serious questions about electoral malpractice, irregularities in result collation, and technical glitches that compromised trust in INEC’s systems. Yet, the judiciary’s ruling was final, leaving millions feeling disenfranchised and unheard.

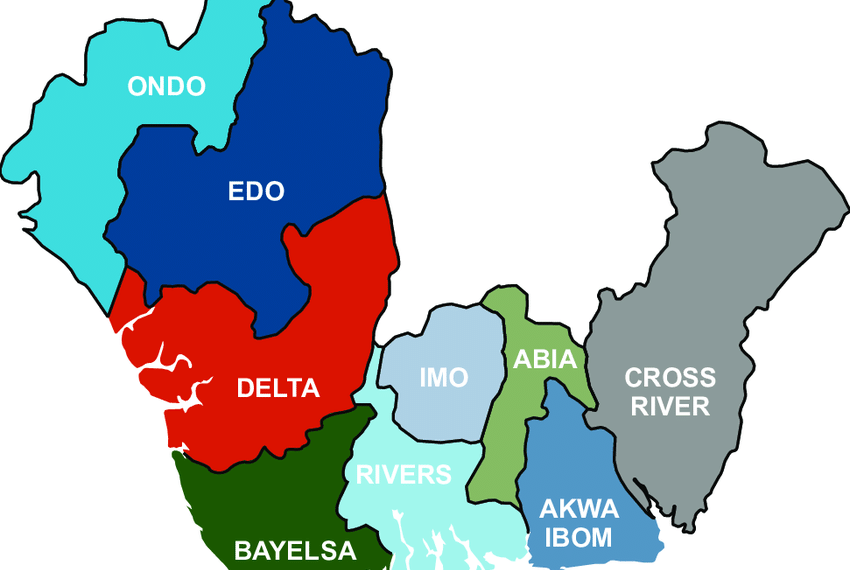

On September 21, 2024, Edo State held its gubernatorial election. INEC declared Senator Monday Okpebholo (APC) the winner with 291,667 votes, defeating Asue Ighodalo (PDP) and Olumide Akpata (Labour Party).

Unsurprisingly, the result was also contested. The PDP and its candidate, Ighodalo, filed a petition challenging the outcome, alleging over-voting and procedural flaws. They presented 19 witnesses and 154 BVAS machines as evidence at the tribunal. Judgment is still pending.

This scenario is all too familiar. Once again, voters had to wait, not on INEC’s final tally, but on the judgment of a panel of justices they were forced to believe were impartial to determine who truly won.

The Judiciary’s Overstretched Role

While the judiciary plays a critical role in upholding justice, its expanding involvement in determining the winners of elections threatens the principle of popular sovereignty. When judges become kingmakers, democracy is no longer “government by the people” but “government by legal interpretation.”

Moreover, this judicialization of democracy erodes faith in both the judiciary and electoral bodies. Even when courts make fair decisions, they are often perceived as politically influenced, especially in a context where trust in institutions is fragile.

The more courtrooms substitute ballot boxes as the final decision point, the more Nigerian democracy is at risk. The people must be the ultimate decision-makers in elections, not legal technicalities, partisan judges, or compromised institutions.

Until INEC becomes fully independent, professionally staffed, and technologically transparent, and until political parties are held accountable for their actions, Nigeria will continue to face contested mandates, voter apathy, and growing disillusionment.

Suggested Call to Action

– Full independence and reform of INEC.

- Strict enforcement of electoral laws with real consequences for fraud and malpractice.

- Transparent use of electoral technologies with public access to results.

- Strengthening civil society organizations to hold institutions accountable.

- Constitutional and legal reforms to limit excessive post-election litigation.

Feature image credit.